The BMC elections on 15 January, 2026 will be a crucial test for the Thackeray legacy in Mumbai, where the Shiv Sena dominated civic politics for 25 years at a stretch. But the city’s changing demographics and economy have had a far reaching effect on its voting pattern.

This year, the contest has taken on new dimensions. The principal contenders are the ruling Mahayuti alliance, comprising the Eknath Shinde–led breakaway Sena faction and the BJP, whose seat-sharing negotiations have threatened to complicate the contest, and a re-energised opposition bloc led by Uddhav Thackeray’s Sena and Raj Thackeray’s Maharashtra Navnirman Sena. A diminished force in the city, the Thackerays are campaigning on a shared ‘Marathi manoos’ plank to consolidate regional support.

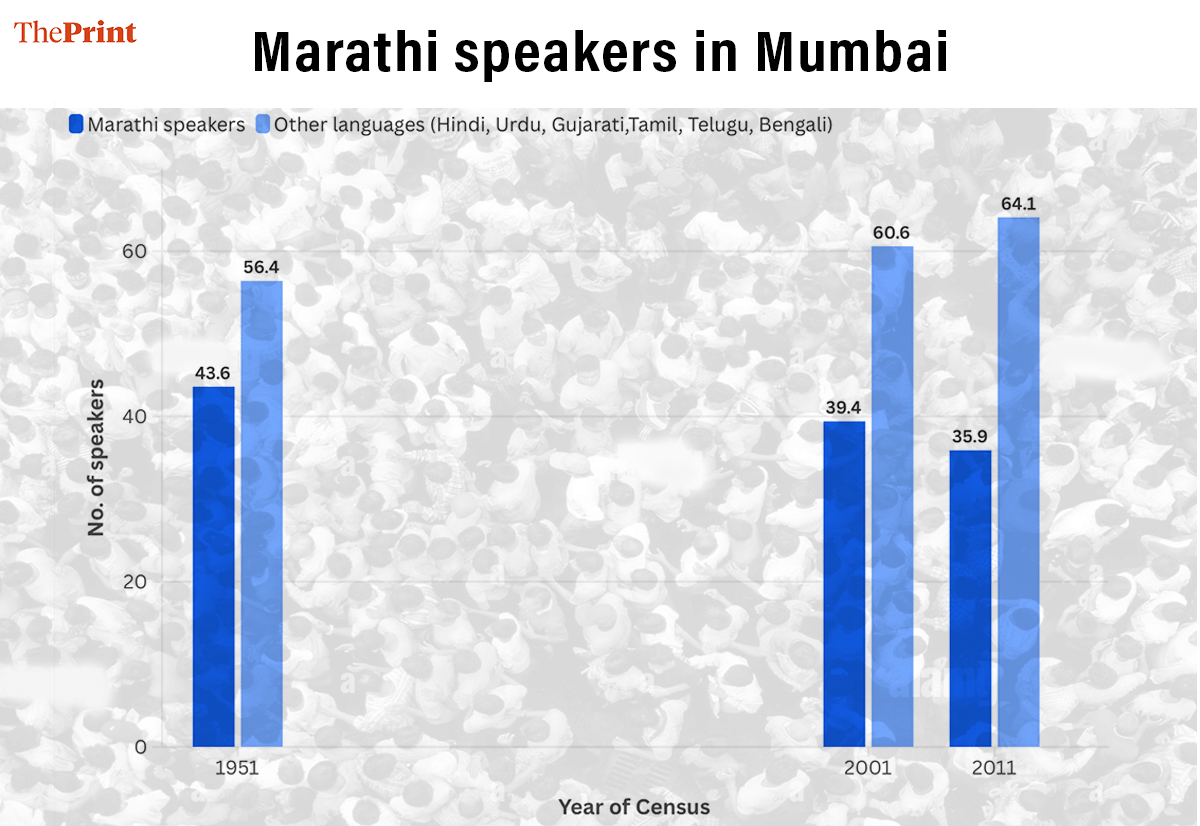

“At one point, Shiv Sena represented the aspirations of a certain linguistic group of people, but their number is going down, and on the other hand, you have another party catering to similar aspirations, irrespective of the linguistic composition, today,” said Uttara Sahasrabuddhe, a former professor at Mumbai University.

The Congress, meanwhile, is struggling to gain traction. Crippled by infighting within its local units, it is set to contest the elections independently. Despite being part of the Maha Vikas Aghadi, it is taking on both the Mahayuti and the Sena–MNS combine.

The Hindi speaking population has crossed, or probably in the next five years will cross, the Marathi speaking population, city chronicler Bharat Gothosakar of Khaki Tours told ThePrint. “That is what will make a difference in the way voting will happen in the city,” Gothoskar said.

He also noted that Mumbai has one of the largest Muslim populations in a non-Islamic country, about 17-18 percent of the voters, and there will also be a huge impact of Muslim votes.

In Mumbai today, no single language is spoken as a mother tongue by more than a third of the population, reflecting its cosmopolitan character. According to estimates by political parties, now the Marathi speaking population could be at 30 percent, very close to the Hindi speaking population.

Historical data illustrates that the dominance of Marathis has declined over time. The 2011 Census showed that Marathis remained the largest linguistic group at 35.9 per cent. Hindi speakers accounted for 22.9 percent, Urdu speakers 13.5 percent, and Gujarati speakers 11 percent, with many other languages spoken in smaller numbers. The 2001 Census had shown Marathi speakers making up about 39 percent of the city’s population, with Hindi, Urdu, and Gujarati speakers accounting for 16 percent, 15 percent, and 11 percent, respectively.

In the early post-Independence period, a report by the Union government–appointed States Reorganisation Commission, based on the 1951 Census, had noted that Maharashtrians constituted 43.6 percent of Bombay’s population. Although they remained the largest group, their share has fallen significantly over subsequent decades.

Also Read: Thackeray cousins reunite: The clan that shaped Maharashtra politics—from Prabodhankar to Aaditya

From Independence to liberalisation

The city was formed 365 years ago. It was always a cosmopolitan city by nature.For the first 200 years, it was a traders’ town, also called Manchester of the East.

Many traders from different parts of India and beyond came and settled in the city: Hindu Gujaratis, Konkani Muslims, Jains, Parsis, Muslim-Khojas, Bohras, Memons, etc.

“For the first 150 years, this was a Marathi minority town. But then, the industrialisation 150 years ago changed it,” said Mumbai-based city chronicler Bharat Gothoskar.

The mushrooming of textile mills was the first phenomenon to change the city. One thing that however has remained constant is migration.

By 1920s—the peak of textile manufacturing in the city—25 percent of the city population was Ratnagiri born.

“Which means half was Konkani/Marathi speaking and half was not. There was no concept of a linguistic state. Other than that, six other languages were spoken here,” Gothoskar said.

And when the division of Bombay state was to take place on linguistic lines, a class divide was taking place in people’s minds as Marathis mostly were blue collar communities.

“At the time of Samyukta Maharashtra, it was an emotional issue where people across party lines participated, but at the same time, it was also about class structure,” said Dr Ajinkya Gaikwad, a professor of politics in Mumbai.

During the 1940s-50s, Mumbai became a protest site. From Quit India movement to Samyukta Maharashtra to labour union protests in the textile mills, the city was bustling with people coming out on roads and fighting for their rights.

After the city got integrated with Maharashtra, 50 percent of the city was Marathi speaking. The issue of ‘sons of soil’ cropped up as employment for ‘Marathi manoos’ became a point of focus. Shiv Sena was thus born in 1966 on the back of a movement led by a young cartoonist, Bal Thackeray.

In the initial days, Sena, which was more of a social organisation than a political party, was in direct fight with the Communists. But slowly in the 70s, the effect of Communists started fading, and Shiv Sena emerged as the political party to reckon with in the 1980s.

During this period, the union strikes at the textile mills were a common sight.Though the mills were owned by non-Marathis, the workers in the mills were lower middle class Marathi people.

“The lower middle class and blue collar workers were pitted against industrialists who were non-Marathis/outsiders,” said Gaikwad. “So, protests and strikes that took place that time were cultural and class oriented, and it was a deadly combination as it put the economy to a standstill as Mumbai was heavily manufacturing oriented,” he added.

With the mills closing in the 80s, ‘Marathi manoos’ who stayed in the chawls of central Mumbai became jobless. The spaces left vacant by the mills were converted into malls, and a business district started flourishing in the area.

The ‘Marathi manoos’ left and settled outside the city limits as their families expanded.

As the economy started to open up, Mumbai’s identity changed from industrial hub to financial hub.

“As manufacturing diversified into smaller units, the number of workers dropped. And hence their power to protest dwindled. Socialists and communists had unions in large factories but that changed over time and it became easy to control workers’ unions,” said Gaikwad.

Neo-liberal period

From the 90s, the city opened up to various economic opportunities and people’s flow into the city started increasing rapidly.

As the job structure changed, the type of migration also changed, said Dr Uttara Sahasrabuddhe, former Mumbai University professor.

“People who used to come to Mumbai for industrial jobs were less educated. Later, those coming into the city were professionally educated. And so the type of people changed, and they brought a political culture different from that of the lower middle and upper middle classes. This took place because of demographic change,” she said.

The city’s Marathi speaking population started dipping and Hindi speaking population started ascending, impacting Shiv Sena.

This also included the Muslims coming from the Hindi belt while the Konkani Muslims’ numbers dropped.

Slowly, Hindi started taking centrestage.

This was the advent of the neoliberal economy where the state apparatus withdraws and lets private corporate takeover.

“This concept revolves around profit rather than welfare and eventually the ethics of the city changes,” said Dr Ajinkya Gaikwad. “It allows us to monetise and privatise everything, because of which, the character of the city changes.”

The larger implication was that people stopped caring about the society and city, and analysts say that the city was okay with not having corporators for many years.

Gaikwad pointed out it could be one of the reasons why people stopped being vocal in the city. To illustrate the point, he gave the example of the air pollution protest and growing environmental activism.

“The activism is in spurts but is the larger section of the city talking about it? Who is talking really about it?” asked Gaikwad.

This is also manifested in the poor voter turnout in the city.

In the 2017 BMC elections, around 55.5 percent of Mumbai’s voters cast their ballots. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, turnout in the city was about 52.4 percent, down from roughly 55.4 percent in the previous general election. The 2019 Maharashtra Assembly polls saw Mumbai voter participation at just over 50 percent. In the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, turnout in the city remained around 52.4 per cent, and data from the 2024 assembly elections indicate a similar pattern of participation, with turnout figures in the low- to mid-50s.

Mumbai South constituency, which has the affluent and elite population, mostly logs the poorest voter turnouts. For instance, in the 2024 Lok Sabha poll, it saw around 50 percent voter turnout, with Colaba registering a dismal 43-44 percent. This constituency houses businessmen, politicians, artists, mostly Gujaratis, Marwadis, and Jains. The suburbs—Borivali, Mulund, Vile Parle, Byculla, and Mahim—registered better turnouts in 2024, in the mid‑50s to low‑60s percent range, reflecting stronger engagement. These areas have a mix of Marathis, Gujaratis, and Muslims.

Rise and fall of Shiv Sena and BJP

Shiv Sena, which started growing in prominence among the Marathi speaking population via various government employment opportunities through the Lokadhikar Samiti, started changing its priorities in the 1980s.

Since coming to power for the first time in the city, the Shiv Sena had started making it more Marathi. “It is to the credit or discredit of Bal Thackeray that he ensured that two thirds of elected representatives were Marathi speaking, and they ensured Marathi speakers became the mayor of Mumbai,” said Gothoskar.

But the city was changing, Bal Thackeray realised that he could not sustain the party on the issue of ‘Marathi Manoos’ in the face of changing demographics. So, the party started catering to the Hindutva ideology, giving a space for BJP to grow along with it. The party had launched Marathi daily Saamna in 1988, and Bal Thackeray, in 1993, launched Dopahar ka Saamna to take the party’s ideology and thoughts to North Indian voters.

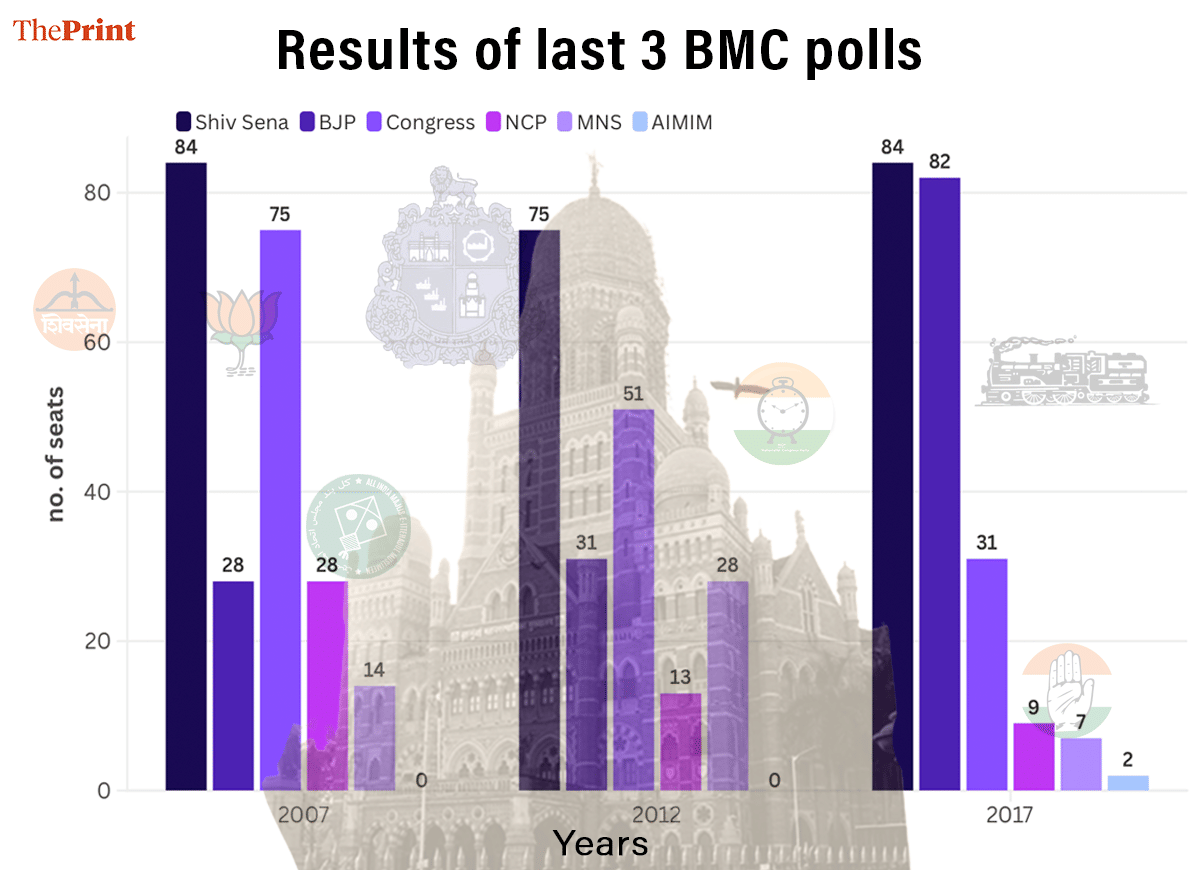

In 1997, when Shiv Sena came to power with BJP in BMC, it started a streak that played out till 2017. By 2017, when both the Sena and BJP fought separately, the latter was already a big brother in the state and could win seats at par with the Sena in BMC—a warning sign.

Meanwhile, what was started by Bal Thackery has continued. Of late, Shiv Sena under Uddhav Thackeray did an outreach programme for Gujaratis in 2022 and also conducted a Raas Garba function. They sent Priyanka Chaturvedi, a Hindi speaker, to Rajya Sabha.

Time and again, members of Uddhav Thackeray’s Sena have said that they are against the violence meted out against North Indians. Raj Thackeray also did an outreach programme for the Gujaratis ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

The focus of governance also changed over time, and when BJP started focusing on developing infrastructure in Mumbai to cater the Gujarati speaking and Hindi speaking populations amid their growing population, other parties followed suit.

What the Congress had tried to do at the state level with planning metros and Navi Mumbai airport, but stopped short. Giving powers to MMRDA (Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority) and expanding Mumbai limits to mirror Delhi NCR were plans from Congress-NCP times, but received a much needed push when Devendra Fadnavis became the CM.

Since many people living on the outskirts of Mumbai were coming to Mumbai for work, the expansion of metros, roads, tunnel networks was a big boost in their everyday travel, which BJP understood, said Sahasrabuddhe.

“This infrastructure push is catering to a new middle class that has migrated and living here for a long time and their long term demands are being catered to and they see this as BJP doing it and hence BJP’s support is growing,” she said.

Gothoskar said that the Hindi speaking and Muslim populations are continuing to rise and the Marathis and Gujaratis are receding.

“So for the first time, somebody will challenge Marathi speaking people in terms of the impact and that is going to be understood based on whether there will be a Marathi speaking mayor or not. That is something unique,” he said.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Internal fighting saw Mahayuti & MVA form unlikely ties in some seats. How they fared in Maharashtra